The original, French-written wersion of this piece is to be found here.

Have you ever heard of Football Manager? In this video game, you’re some kind of super coach, as found in English soccer clubs. You define your team’s tactics, oversee training sessions, sell and buy players and so on. Years from now, when I started playing Football Manager, the game wasn’t exactly user-friendly. Each player was described as a plain stats list (looking just like a soviet-union Excel spreadsheet), matches were rendered in text mode only (“Zidane gets the ball”… “Zidane dribbles” … Exciting, isn’t it?), and the sole satisfaction was to see the young striker you bought for a couple bucks in Moldavia’s C-League gain financial weight as he got better on the field.

Yet if I ended up parting with my Football Manager CD, it wasn’t out of sheer disgust – on the contrary. In fact, this game had such an effect on me that it frightened me a bit.

I regularly happened to start what I thought would be a quick game session before bedtime only to come back to reality the next morning, birds tweeting outside as to celebrate my Champions League victory. I played before going to work; I played all weekend long, I played on my laptop on the train, in the car… Those among you who regularly spend time playing video games will recognize these symptoms, but they may not know the pathology’s name. I was “caught in the flow.”

Before we go any further, time for some quick theory.

The concept of “cognitive flow” was formalized in 1970 by the Hungarian psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi. According to him, our emotional mindset is directly influenced by the relationship between our skill level and a task’s difficulty. To summarize, if the task is too complicated, we may feel anxious, and if it is too simple, boredom prevails. But when we have just the right skill level to accomplish what is asked, we enter the famous “flow” state.

Also according Csíkszentmihályi, it’s quite easy to recognize a user who’s in the flow. She would be highly concentrated, have a sense of control and mastery. She would also be convinced that the challenge and effort demanded to complete the task are the only necessary justifications to its completion (this is called an autotelic activity: an activity that justifies itself). In the most extreme cases, the user would experience a loss of self-awareness and a distorted perception of time.

That’s Football Manager’s strength: it brings the player to a state of perfect flow. How does it achieve that? Well to answer this question, let’s turn to Csíkszentmihályi again, as he identified four characteristics shared by all flow-prone tasks:

- They include concrete goals along with understandable rules,

- The things we have to do in order to achieve these goals are related to our capacity,

- We’re provided with clear and temporally relevant feedbacks, so we’re kept aware of the objective’s fulfilment at all times,

- And external distractions are reduced to keep us focused.

And indeed, this accurately describes my Football Manager player experience. But now that I stopped playing, I have lots of free time. So I happen to surf the web and browse for interactive documentaries, for instance. Trust me: most of them are much, much more beautiful and approachable than Football Manager. They often have interesting topics, great graphic design, eye-catching images, and are almost always packed with good ideas UX-wise. And yet, interactive documentaries’ average consultation length is shockingly low: in France, it’s very rarely above twenty minutes (more often between 5 and 10), for pieces that often encapsulate hours of video. Even I, although being an I-docs enthusiast, often give up faster than I would have liked, as I feel I’m drowning in a “tsunami of information” (I try to define this concept in this presentation ).

Many interactive documentaries put me in a state of anxiety (“There are too many things to see, I do not have enough time, I’m afraid I might miss something important …”), thus failing to catch me in the flow.

Of course, I-docs are not video games, and I don’t pretend they should be (at least not in this piece). But Csíkszentmihályi’s work is not specific to games: according to him, any task can catch a user in the “flow.” Surely, consulting an interactive documentary could be seen as a “task”, browsing through all of its content in a non-linear way being the user’s ultimate “objective”.

Starting from there, I asked myself a simple question: is there something we can learn from the flow theory and its application to video games design in order to improve interactive documentaries’ user experience?

1) Set concrete goals along with understandable rules

Let’s face it: not every Internet user has the same “interactive literacy”. There is a fair chance that a hardcore video game player will understand an interactive object faster than, say, my uncle (he lives in the countryside and bought his first computer 6 months ago). But one thing is certain: give a user too much information at a time and you’ll confuse her, no matter how skilled she is.

Worse, if you provide your user with information on two different subjects at the same time, a conflict occurs that diverts her attention and causes her cognitive abilities to crumble. The result? Immediate frustration, loss of flow – in our case, this could be summed up as “Well I’d rather close this tab and go watch lolcats videos on Youtube” (a far easier task if there is).

That’s why things have to be crystal clear for your interactive documentary user. What is the goal? Well the goal is for her to see all the documentary resources there is to be seen. What are the rules – or, to put it differently, how will she able to reach the goal? Well, the user interface has to answer this question in a non-ambiguous way.

That’s why you’ll need a limpid design. Everyone should be able to get as quickly as possible a sense of the task that lies ahead – for instance, it should be possible to identify how many videos your iDoc encapsulates and how long they are.

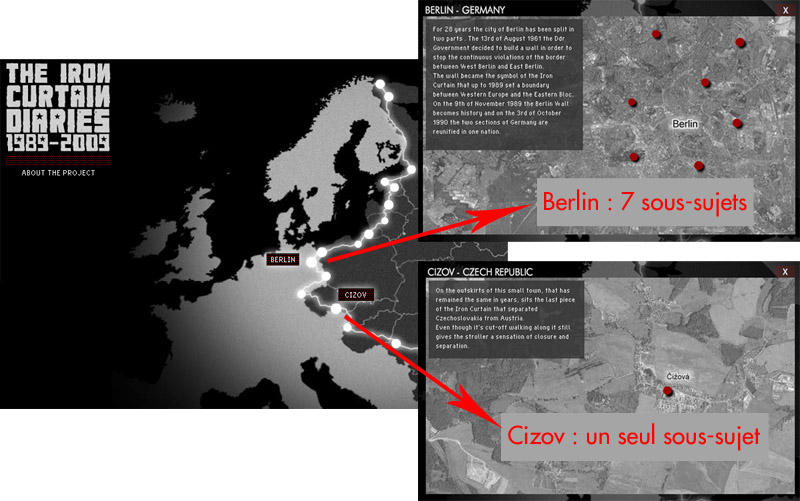

Let me clarify this with an example. Iron Curtain Diaries is an interactive documentary that invites us to walk along the Iron Curtain, 20 years after it crumbled. Since the moment the user logs in, pellets placed on a map along the east/west border indicate that there are 17 locations to be visited. Nice’n’easy, right? But should the user click on one of those, things get complicated.

In fact, depending on the location, there’s a great variation in the number of sub-contents – and thus, in the time needed to “visit” a location entirely and reach the “goal” of the iDoc. That’s no big deal – but the annoying thing is, nothing on the interface warns the user about it. Using the same graphic representation for different content sizes complicates the user’s experience, as it impedes any estimation of the magnitude of the task. One could for instance have drawn pellets of varied size; in proportion to the number of contents they give access to…

Keep one thing in mind: if your interactive documentary is organized in a non-linear way, any curious user will tend to enjoy clicking everywhere to explore it. But this freedom is double-edged: if there are too many opportunities, the user can quickly feel lost, overwhelmed. Just because your interactive documentary is non-linear, that doesn’t mean you should forsake the user. If she wonders what she “must” do, and if the interface doesn’t provide any obvious answer, then it’s inevitable that she will drop out of the flow.

Therefore, organizing content by groups (like the cities in Iron Curtain Diaries) is an excellent idea. This provides the user with a series of rewarding experiences («That’s it, I watched all the content about Berlin, now I can move on to Gdansk»), thus encouraging her progression in your narrative. But to keep things flowing, this organization needs to be blatant, and any progress should be stressed – you could for instance offer a “reward” for each completed step. Back to Iron Curtain Diaries, the completion of a “level” (the user has seen all the contents related to a location) could for instance provide access to a specific item (a selection of relevant links, an author’s commentary…). It might even have been relevant to show the 17 cities on the map at the beginning of the experience, but to “lock” most of them, thus giving an autotelic feel to the user’s consultation (“If I watch all the Berlin-related content, I’ll be able to access Gdansk !”).

Let’s introduce the next point by going back to video games recipes for a while. Generally, game designers avoid providing the player with important information when she is busy doing something. For example, your attention is rarely drawn to a new quest as you’re in the midst of an epic battle against a level 50 dragon – defeat the monster first, then we’ll talk. There’s a very simple reason to this. When two pieces of information collide, they create a diversion that can have a catastrophic effect on the user’s attention.

Yet that kind of conflict is often seen in interactive documentaries. I picked Amour 2.0 as an example, but there’s plenty more. ![]()

Conflicting information: the “dig deeper” popup diverts from the expert’s speech.In this interactive documentary, you can watch and listen to experts talking about love and its psychological mechanisms. But once in a while, a popup will appear on the documentary subject’s timeline, to provide the user with more information on a particular topic. That’s a nice effort towards deepening the user’s understanding, but it sadly is counterproductive flow-wise.

It takes too much effort for someone to stop listening to an interview, browse some other content, and then go back to the main topic. Of course, one may choose to just ignore the pop-ups. But still, they are designed to be noticed, and as such, they’re a threat to the user’s concentration – which is already challenged by the long-lasting, focus-demanding video interviews.

Would you want to provide the user with more information, it would probably be more appropriate to grant access to it only after the main subject’s over. In fact, this could even be a good way to enforce the point mentioned above: this additional information could be used as a “reward” the user would get before she’s sent back to the main video selection menu. Obtaining this reward would validate the user’s progress, thus encouraging her to keep browsing your iDoc.

2) Don’t ask users more than what they’re able to do

As Csíkszentmihályi points out, there are two reasons for someone to drop from flow state: anxiety – when the task’s too complicated – and boredom – when it’s too easy. Speaking of interactive documentaries, the first scenario occurs far more often than the last. This is probably due to the form’s relative newness, and the lack of audience habits.

Jumping from a classic, linear documentary to a non-linear object demands a huge cognitive effort, to which most of us are not used yet. If the user gets what she “should” do but fails at doing it, then the experience becomes frustrating: stress affects the flow, and the desire to persevere in the interactive documentary’s exploration crumbles.

Of course, not everyone has the same level of “interactive literacy”, the same reflexes and habits when facing interactive objects. In video games, this issue is addressed in several ways. The player is for instance helped through tutorials, and she may chose the game’s difficulty level – nowadays, some games are even able to analyze the player’s behaviour and automatically adapt to her skill level, keeping her challenged but not frustrated.

Once again, I’m not saying that interactive documentaries should go that far. But it is nevertheless possible to provide the user with multiple, more or less complex modes of consultation.

Prison Valley , for example, existed in a plain, linear, easy-to-watch form, that was broadcast on TV (this would be a game’s “easy” mode). It also was an interactive program on the web, in which the user would watch the same story, but could also decide to access specific, detail-focused sub-stories (that would be a game’s “medium” mode). And last but not least, as it went online, the web program benefited from a few months of editorial events. At scheduled times, the user could log in to chat with the documentary’s authors and main protagonists and ask them questions (this would be the “difficult” mode, as it requires a very high user engagement level).

There are other ways to take the user’s abilities into account, or to even help her “level up” in the course of her consultation. One can for instance organize content according to their accessibility level. Ask the user to watch short video modules first, then make them dive into longer ones, interact with simple dynamic slideshows, manipulate interactive data visualizations, and finally play a related “Newsgame” (a potentially complex experience for someone who’s never played a video game before)…

Each new step would come with a small “tutorial”, in order for anyone to understand the task. The user would thus get a feeling of progress in their mastery of the interactive object as she gets more and more documentary substance. A good example of this step by step progress is found in the excellent Lazarus Mirages, in which each new documentary piece includes a new interactive “challenge”.

Another good idea would be to use widespread, familiar symbols to make your users feel at home and bring them to more complicated, unusual interactions. This is what Gol! Ukraine # 2012 does: it uses anchormen, as seen on television. The two characters, Oleg and Katya, speak directly to the user. They welcome, guide and reassure her during her consultation. They also introduce each documentary piece with important contextualization elements and keep users in the flow. ![]()

Oleg and Katya are the two Gol! # Ukraine2012 anchormenNon-linear iDocs are by definition interactive objects (forgive the truism). This means that a significant part of the meaning building process will happen directly in the user’s brain. As they’re free to watch the documentary pieces in the order they want, it’s up to them to link the assets together and reconstruct the author’s point of view – in fact, they even become, to some extend, their own experience’s authors. The power a linear documentary author has over her public through video editing and control of the dramatic arc is partially lost in iDocs. It is replaced by the delicate expressiveness of interactivity. Interactivity becomes a means of expression for the author to master.

This is a key point, as it is extremely difficult for a designer to anticipate the user’s perception of an interactive experience. That’s the reason why game designer proceed through iterative design and organize playtest. There’s no reason for iDocs designers to do otherwise: if you want to know how your interactive mechanics are perceived, you really should consider having a sample of your target audience trying them out.

In video games, playtest arrive in the very early development stages: it is not uncommon to test core game mechanics using paper prototypes, even before a single line of code was written. The same method can be applied to a web documentary, and there are many tools that can help you set up cheap interactive mock-ups throughout the production steps. You’ll thus be able to show them to test groups and gather their feedback.

This is probably the most effective way to identify what works and what doesn’t, to tune the level of involvement you can demand from your audience… In a nutshell: to be sure you’re actually design a flow-prone iDoc.

3) Set up a clear and timely feedback system

Offering a non-linear interactive experience is a risky business. The higher the freedom level (“I can click wherever I want”), the lower the obviousness level (“Where the heck should I click next?”). But there are effective ways to avoid that kind of user confusion. They should at any time know what part of your documentary they have already seen and what remains to be discovered. They also need to have a clear sense of their actions’ effects.

Again, video games are a good example: they are generally rich in all kinds of signs that help the player understand her actions have been taken into account. Attack an enemy and you’ll trigger an animation that shows the damage you made; as soon as you press the “run” key, your character’s walk sound pace up; and should you clear four lines at once during a Tetris game, your score counter goes bananas, stressing without the shadow of a doubt that you’ve achieved an important goal.

Of course, this craft of feedback design as an antidote to user bewilderment when interacting with a complex interactive object can also be applied to iDocs. Some very simple systems have already proved effective – see, for instance, the small grey “vu” (“seen”, in French) mentions that appear to flag already viewed videos in Vies de jeunes .

Simple, efficient feedback in Vies de Jeunes.Thanks to some coding, feedback can obviously be a little richer than that. In Gol! Ukraine # 2012, for example, a user who decides to browse back to the main menu before a video ends will be humorously lectured by a sad anchorman (“It seems you didn’t like this documentary piece… Sorry about that, but don’t worry, we got plenty more for you to watch!”). One could even design system analyzing the user’s choices and providing her with conditional feedback: “According to the videos you watched, you may want to take a look at this piece now, the topics being related…” Lots of social websites (such as the flash gaming platform Kongregate) do this, but the correlative links sometimes are a bit artificial. It would be more suitable to an iDoc’s clearly framed perimeter.

Giving a user feedback on her actions is of course useful in order to reassure her: yes, she is “doing it right”. But it also serves another purpose: to convince her that her consultation of the interactive object really is personal, maybe not unique, but at least tailored to her inputs. Thus the user’s involvement level remains high, and she has a much higher chance of staying in flow state.

Let’s not forget that interactive documentaries are often filled with hours of content. So while you’re designing feedback loops, don’t stop at the step-by-step level. Try to also provide your users with tools so that they would keep track of how much of your iDoc they’ve seen. Display completion percentages, gauges fulfilling as the user watches documentary material… any feedback form relevant to your documentary’s subject is fine, so use your imagination. Why not give them bits of a big picture each time they achieve something, like some kind of jigsaw puzzle they would feel compelled to complete?

To be truly effective, any feedback must meet three conditions:

- They should appear early in the iDoc’s consultation, so the user becomes familiar with them and understands their interest quickly.

- They should appear at the right time: directly after a task’s completion (at the end of a video, for instance), or halfway through accomplishing this task.

- They must be persistent from one visit to the next. When an interactive documentary pleases the user, she could want to come back later… If you saved her progression (through cookies, Facebook connect, registration…) there’s a far higher chance for her to get back to flow state.

4) Lower external distractions

IDocs are demanding interactive objects. They present the user with multiple resources, and ask her to “fill in the blanks” trough her browsing of the content. This complex task is made even harder when the user’s attention is “polluted” by external stimuli. It is therefore important to pay attention your interactive documentary will be integrated in the website that hosts it.

Most of these objects come with a “full screen” mode. This is great, because it greatly helps the user to focus on the documentary only. But not every user will enable this mode – think about people who are at work and want to be able to switch tabs, should their boss pop in. This is the reason why you should as much as possible avoid to surround your embedded iDoc with ad banner, outbound links, info widgets or all kind of stuff that often pile up on news sites pages.

On a same note, it is essential to ensure a good video stream quality. If your iDoc’s videos are constantly interrupted by a “loading” icon, or if they’re so compressed that the images look like cubist paintings, forget about keeping users in the flow. Fortunately, high-speed Internet connexions nowadays tend to limit these risks – but don’t be too greedy, and think twice before embedding full HD videos, for instance.

For the same reasons, your video player’s interface should be as minimalist and inconspicuous as possible. Try hiding it when the user’s mouse pointer is inactive, so that the video grabs all the attention. Don’t forget that the human eye is particularly attracted to animated elements, such as video progress bars. Speaking of which, if in a particular situation you wish to point one of your interface’s features out (the full screen mode, for instance), you could consider animating the related pictogram.

You should also try to take into account the context in which your web documentary will be consulted. The user will often discover it on his work computer, for example during a quick break. There’s no way she’ll then spend much time on it. It is therefore necessary to allow her to easily run back into it later on, when she’ll have more time on her hands.

Let’s face it: mobile devices such as tablets seem to be the ideal devices when it comes to consulting an interactive documentary. Your users will be far more likely to enjoy your work while lying on their cosy couch than nailed to an office chair in front of their computer. But my guess is it is still a bit too early to rely solely on this diffusion model: currently, less than 10% of French households own tablets, and if the figure is higher in the US, it is still far from 100%. The figures for connected TV, which could allow entire families to browse interactive contents together, are even lower. For the months/years to come, you’ll have to figure out alternative ways to bring users back to their computers. Consider sending them a direct link via email, offer them bookmark solutions, identify them with cloud ID systems such as Facebook connect and what not. Lazarus Mirages’ content, for instance, was released in short episodes, and each time each registered user received a message to remind her to come back and check out what’s new – the result was very effective. Social networks can also be powerful update advertisers.

Conclusion:

Interactive documentaries are still a blooming form. Many things are still to be invented, the user’s habits are not clearly defined yet, and each new project brings its share of innovations. And even though I quoted video games a lot in this article, I docs are not intended to become games: they do not work on the same mechanics; they motivate users in very different ways. Still these two media share many similarities, the first of which being that they’re interactive to the core. And undoubtedly, video games that captivate players for hours do so because they catch them in their flow. Learning lessons from its venerable grandfather (the first video game dates back from the early 60s!), the interactive documentary form can become a powerful media too, and help XXIst century documentary filmmakers to share their point of view on the world.

I’ve spent most of this already far too long article speaking about how the flow theory could be applied to interactive documentaries. I would now like to talk about the “why”. This piece’s original, French version gathered a lot of good comments, but some people were a bit frightened that I would, thanks to video games recipes, try to lure people into paying attention to things they’re not really interested in. I understand this concern, and I think I have a sense of where it comes from. Some people, especially non-players, tend to consider video games with a cautious stance. They’ve heard about stories of addiction, and sometimes they don’t get how gamers can waste lots of time in such a non-productive, even alienating activity, just for the sake of meaningless fun.

The question of whether a videogames related addiction actually exists is a very complex one, and I don’t feel competent enough to answer it. But for me, being in a flow state and being addicted to something are two very different things. On the one hand, there’s a set of formal, design-related techniques aiming at helping the user to delve into a subject. On the other hand, there’s a psychological overreaction to a piece of software a little too well designed.

The flow theory is not specific to video games. It may be applied to, let’s say, books: why do pages come with numbers, if not to give the user feedback on its progress in the “task” reading is? Why were new fonts drawn, if not to facilitate letters deciphering and reduce distractions that could distract the reader? You can also, for example, apply the flow theory to a feature film and chop it into shorter, easier to watch, individually coherent videos that tell a big story when you watch them in a row – it actually already exists and it’s called a TV show. It doesn’t mean all books or all TV series are “addictive”, even if some actually are (I still remember watching all the episodes of “24”’s first season in 3 evenings – and feeling exhausted at work because of it!)

The same thing goes with interactive objects, be they video games, interactive documentaries, interactive dataviz and what not. Not all of them are “addictive”. Not all of them are “fun”. In fact, video games I enjoy nowadays tend to be a bit depressing – see ImorTall, for example: http://www.kongregate .com / games / Pixelante / immortall Not all of them do, like Farmville does, use behaviourist mechanics to hook you and steal your money (my opinion is that there is an ethics of video games, and that Farmville is not an ethical game, but then again, that’s another debate).

But all the “good” games have one thing in common: they’re well enough designed to put you in a flow state. They make your task a little easier.

But is it a good thing to make things easier? Let’s put it straight: there’s no way you’ll deceive your users and “addict” them to your iDoc (I tip my hat to the designer who achieves such a feat without using hypnosis). No, it is relevant to try to make things easier for your user because interactivity is both a strength and a liability.

It’s a liability because no matter what you do, it will always be easier for a user to receive a “message” in the form of a speech. That’s what television, newspapers and radio do: a journalist tells a story, and the “public” listens to it, or refuses to listen. But you don’t need to “do” anything apart from listening in order for you to receive the message. Interactive objects are redefining the situation: they are not a speech, but a discussion. This is the very definition of the word “interactivity”. Now, “discussion” means “efforts”, and it is never easy to get someone to make an effort, especially on the Internet, especially to when talking about documentary content.

So in that case, why even bother conceiving iDocs? Well, from my point of view, it all boils down to exploring new paths. This paradigm shift, this move from using rhetoric to actually having a discussion (be it limited framed, as in an iDoc), that’s an extraordinary opportunity for journalists and documentary “filmmakers”. That’s really using what the Internet (and interactive devices such as PC, Smartphone, tablets…) provides that “older” media (the press, radio, TV, photography) don’t. This is a chance to finally give the very people we are talking to a role in our attempts to describe reality.

This is the opportunity to allow them to understand things through experimentation, exploration, choices, empathy… Tools that were unknown to journalists until recently. Here lies the true power of interactivity. But to use this strength, we must learn to control it, as our predecessors have, over the years, learned to master the delicate craft of writing for the radio, the fine art of video editing or the science of using the right figures of speech and write compelling news stories.

I’ve been playing video games for quite a long time now (20 years of practice, oh my), and the feelings I got during the hours I spent being captivated by play and interactivity are not that far away from the feelings I got after reading or watching movies. I sometimes had the impression of having “wasted my time”, to have diverted myself (as Blaise Pascal defines it): when I played no-brainers such as Angry Birds, when I red tabloid press, when I watched reality TV… But I also lived extraordinary experiences that have profoundly affected me, and I am pretty sure they were specific to each media form. Bioshock’s existentialism cannot be compared to Romain Garry’s Your Ticket is no Longer Valid’s. But one is not better than the other: they’re simply not transmitted the same way.

Today, I’m really eager to explore interactivity as a form and to understand how it could be used to the best of its potential. With a simple aim: to invent new, different, more engaging ways of transmitting information.

Florent Maurin

This article was greatly inspired by Sean Baron’s excellent Cognitive Flow: The Psychology of Great Game Design.